The Top 3 Trademark Cases in Switzerland 2022

Key takeaways

- ...from Lindt & Sprüngli vs. Lidl:

A survey, which has been scientifically conceived and correctly conducted with regard to the persons questioned and the methods used, is the most suitable means of evidence for proving trademark assertion under trademark law in civil proceedings. - ...from PUMA WORLD CUP QATAR 2022 et al. v QATAR 2022 (fig.) et al.:

The combination of venue and year of an event is widespread, particularly for sporting events. The public understands such a designation as a description of the sporting event itself and not as an indication of its organizer or the origin of the products designated by it. - ...from UNIVERSAL GENEVE v. BEAU HLB:

The prior use of a trademark in Switzerland does not prevent the presumption of subsequent "export use" of the same trademark within the meaning of Art. 11 (2) of the Trademark Protection Act.

Introduction

2022 has resulted in numerous interesting court decisions on trademark matters in Switzerland. We have selected three cases that we consider of major impact for Swiss trademark practice. Please, read below why.

The most internationally reported case: Lindt & Sprüngli's Golden Chocolate Bunny enforced against Lidl

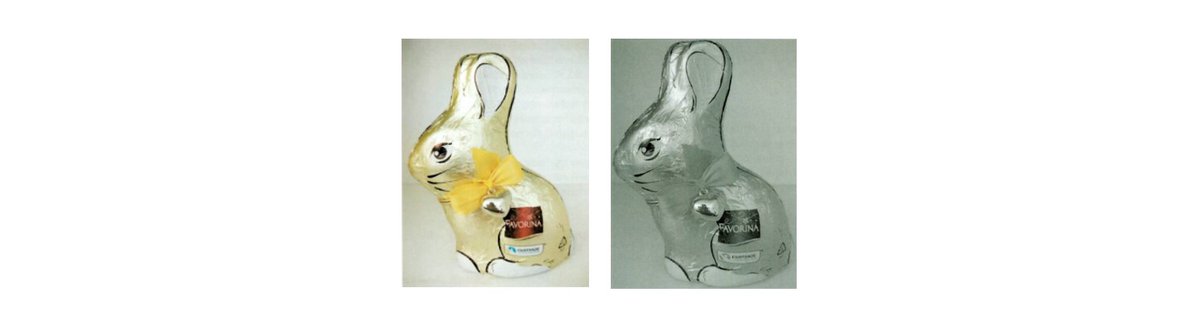

In Lindt & Sprüngli v. Lidl (Case 4A_587/2021 of the Swiss Federal Supreme Court from August 30, 2022), the Swiss Federal Supreme Court was tasked with deciding infringement claims brought by Lindt & Sprüngli against Lidl, based on two three-dimensional trademarks (below, illustrations A and B), demanding a ban on Lidl advertising, offering or selling its alleged infringing chocolate bunnies – be it wrapped in gold foil or in a different color (below, illustrations C and D). In this context, the court also considered a counterclaim for invalidity of the three-dimensional Swiss trademark registrations that had been raised in defense to the claim for infringement by the sale of the competing products.

Lindt & Sprüngli argued that the chocolate bunny marketed by Lidl was very similar in form and design to its own three-dimensional bunny trademarks – and could be confused with them, which infringed its trademark rights. According to their own representation, Lindt & Sprüngli had sold such chocolate bunnies wrapped in gold-colored foil in practically unchanged form and design since 1952. Lidl, on the other hand, raised the defense that Lindt & Sprüngli's trademarks belonged to the public domain and were, for this reason, excluded from trademark protection (see Art. 2 of the Swiss Trade Mark Protection Act (TmPA)).

In a first step, the court examined whether Lindt & Sprüngli's form marks were indeed protected under Swiss trademark law because they have become well established on the market. According to Art. 2 (a) TmPA, trademark protection is excluded for signs that are part of the public domain, unless they have gained secondary meaning as trademarks for the claimed goods and services.

This condition is fulfilled if a significant part of the addressees of a product understands the sign as an individualizing reference to a specific company. To prove such acquired distinctiveness, representative surveys of the relevant public can be used in addition to evidence of the many years of significant sales or intensive advertising efforts.

WHY IT MATTERS |

|

Lindt & Sprüngli provided such surveys, which attested to the Lindt Gold-Bunnies having a very high level of recognition. Lidl, in this context, claimed the filed surveys to be private expert opinions, without evidentiary value. This notion was based on the Federal Supreme Court's case law on the admissibility of private expert opinions as evidence in civil proceedings, which states that private expert opinions do not have the quality of evidence, but only of party assertions. Based on Lidl's position, the lower court had qualified the submitted survey results as private expert opinion, and thus were considered mere party assertions and not evidence. As a result, the lower court had considered the evidence of trade acceptance as unsuccessful. With regard to surveys under trademark law, however, this case law was already outdated before the respective judgment. Rather, according to the Federal Supreme Court, such demoscopic surveys are the surest means of proving acquired distinctiveness. The Federal Supreme Court therefore considered that the lower court's conclusions not only contradicted federal case law but also ignored the specifics of trademark law. In addition, the Federal Supreme Court considered that it is incoherent and neither procedurally economical nor cost effective to deny, from the outset, any evidentiary value to survey evidence in civil proceedings; this holds true especially when the parties must obtain these (costly) surveys to prove the sign's trade acceptance, according to Art. 2 (a) TmPA in registration proceedings. The court concluded that a demoscopic survey submitted as a party expert opinion is not to be qualified solely as a party submission:

"A survey, which has been scientifically conceived and correctly conducted with regard to the persons questioned and the methods used, is suitable; indeed, it is the most suitable means of evidence for proving trademark assertion under trademark law in civil proceedings. This is true regardless of the fact that it was introduced into the proceedings by a party. It is a document suitable to prove a legally relevant fact..." (machine translation)

The court also considered the methodological doubts Lidl raised, such as the fact that the surveys, which had been conducted on the internet, were unfounded. Also, demoscopic surveys conducted online may be suitable as evidence. Consequently, the Federal Supreme Court adhered to its previous case law and considered the proof of trade acceptance, based on the outstanding results of the demoscopic surveys, to be established.

The Federal Supreme Court further held that, regardless of the previous considerations, clearly Lindt & Sprüngli's form marks are associated with the company by a very significant part of the public. Therefore and irrespective of the quality of the evidence of the demoscopic surveys, the court held that it can be assumed that Lindt & Sprüngli's form marks are notoriously distinctive. The Federal Supreme Court thus affirmed the protectability of the signs in question under Swiss trademark law.

The Federal Supreme Court then examined if there was a likelihood of confusion between the three-dimensional trademarks of Lindt & Sprüngli and the products sold by Lidl. In its reasoning, it stated that Lindt & Sprüngli's form marks, as signs with a particularly distinctive character established in the trade, leave behind formative memories, to which the marketed Lidl bunnies are strongly and misleadingly related. Also the label 'FAVORINA' printed on the Lidl bunnies (see illustrations C and D above) does not change this. Labeling may, under certain circumstances, provide sufficient differentiation from other products with similar features. However, even if the label 'FAVORINA' distinguishes the Lidl bunnies from Lindt & Sprüngli's bunnies, it cannot be assumed without further ado, especially in the case of foodstuffs, that the buyer, acting with average attention, will orientate herself by reading the label. Rather, pursuant to the court, the buyer will choose familiar products based on their form and features. The court recognized that there were also, in fact, other differences between the three-dimensional trademarks and the Lidl chocolate bunnies. It concluded, however, that there was a likelihood of confusion, since also these other differences between the two shapes or designs, in particular the decorations and ornaments belonging to the public domain, did not have any function of indicating origin and were not capable of eliminating the likelihood of confusion. The above applies not only to the black-and-white comparison with the mark registered without color claim (No. 696955), but equally to the mark with color claim "gold, brown, red" (No. P-536640). The broad, averagely-attentive public will not be able to distinguish the slightly diverging shades of gold in their memory, and neither will the different colors of the meshes and pendants or the wine-red color of the 'FAVORINA' sign lead to sufficient distinctiveness.

Based on the foregoing considerations, the Federal Supreme Court upheld Lindt & Sprüngli's claims and affirmed the prohibition rights according to Art. 13 TmPA. Lidl was consequently prohibited from advertising, promoting, importing, storing, offering and/or selling the relevant products in Switzerland. Furthermore, the destruction of the Lidl gold bunnies in Lidl's possession was ordered.

The war for event trademarks: FIFA and PUMA fight for World Cup Qatar 2022 trademarks and both fail

In PUMA WORLD CUP QATAR 2022 et al. v. QATAR 2022 (fig.) et al. (Cases 4A_518/2021 and 4A_526/2021 of the Swiss Federal Supreme Court, April 6, 2022), the Federal Supreme Court had to decide on invalidity claims that FIFA had initially raised against PUMA's trademark registrations "PUMA WORLD CUP QATAR 2022" and "PUMA WORLD CUP 2022." PUMA had counterclaimed for invalidity of the two FIFA trademarks "QATAR 2022" and "WORLD CUP 2022" in the same proceedings. Hence, the Federal Supreme Court's decision concerns the validity of four trademarks in total.

By way of background to the case, FIFA was the owner of the two figurative trademarks:

In 2018 PUMA registered the word marks "PUMA WORLD CUP QATAR 2022" and "PUMA WORLD CUP 2022". Thereupon, FIFA filed a lawsuit against PUMA before a civil court, requesting the cancellation of the two trademarks, which it said were misleading and thus void. In addition, FIFA asked for an injunction to use the two marks in the course of trade in connection with accessories, clothing, sports articles, etc. PUMA filed a counterclaim demanding cancellation of the aforementioned FIFA trademarks, arguing that they lack distinctiveness. The lower court dismissed both claims, by finding PUMA's two trademarks not to be misleading and FIFA's trademarks to be distinctive. Subsequently, both parties appealed the decision to the Federal Supreme Court.

WHY IT MATTERS |

|

According to Art. 2 (c) of the TmPA, misleading signs are absolutely excluded from trademark protection. This provision is intended to prevent misleading signs from impairing competition, in particular, market transparency. For the assessment of whether a sign is misleading, the only decisive factor is whether the indication is objectively capable of arousing false ideas or expectations in the buyer about the marked offer. Such risk of misleading information can inter alia be based on the fact that the sign leads to an incorrect conclusion about the business circumstances of the trademark owner.

In its judgement, the Federal Supreme Court first dealt with the validity assessment regarding PUMA's trademarks. It held that from the elements, "PUMA" and "WORLD CUP QATAR 2022" or "WORLD CUP 2022," expectations of a special relationship arise between PUMA and the FIFA World Cup 2022. The average Swiss consumer will assume that the designated products (in particular sports articles, clothing and accessories) originate from a company that is a main sponsor of the FIFA World Cup 2022 in Qatar. The court also held that it is probably correct that the use of the terms "WORLD CUP QATAR 2022" or "WORLD CUP 2022" will not be understood as a reference to FIFA's goods and services, but is descriptive. According to the court's assessment, however, this does not change the expectation of the targeted public, which is triggered by the association of "PUMA" with these terms. The court further pointed to the fact that PUMA was neither an official sponsor or partner nor was it an (co)-organizer of the FIFA World Cup 2022 in Qatar. The two signs at issue therefore raised expectations in the relevant public, which are disappointed, and must thus be regarded as misleading.

Moreover, the court held that the misleading effect is not removed by the use of the additional word "PUMA," which is an element not objectionable in itself, in giving the trademark a distinctive character. It recalled the fact that the misleading character of a sign is an absolute ground for exclusion, which is not to be assessed with reference to another sign or exclusive right of a third party.

In sum, PUMA's trademarks were deemed misleading. They were therefore excluded from trademark protection under Art. 2 (c) TmPA and consequently cancelled from the registry on the basis of Art. 52 TmPA.

With respect to the counterclaim, PUMA argued that FIFA's two word/figurative marks "QATAR 2022 (fig)" and "WORLD CUP 2022 (fig)" (see above) were not distinctive and protectable under Art. 2 (a) TmPA. For its assessment, the Federal Supreme Court referred to its established case law, according to which a sign is protectable as inherently distinctive if, due to a minimum original distinctiveness, it is capable of individualizing the goods and services it designates and thus enables the consumer to recognize them in the general range of similar goods and services.

FIFA did not dispute that the word combinations "QATAR 2022" and "WORLD CUP 2022" by the target public will be understood as a reference to the Football World Cup to be held in Qatar that year. The court argued that the combination of venue and year of the event or "World Cup" and year of the event is widespread, particularly for sporting events, and it is readily perceived as a reference to the sporting event taking place in the year or place in question. It therefrom concluded that the public understands such a designation as a description of the sporting event itself and not as an indication of its organizer nor of the origin of the products designated by it. According to this assessment, the court concluded that the two trademarks were to be considered directly descriptive for the sporting event itself and for the goods and services associated with its organization. Also, in the Federal Supreme Court's view, the addition of a zero in the form of a stylized football in each of the disputed signs does not alter that fact. The figurative element, which is directly descriptive and banal in its graphic representation, is not capable of giving the signs the minimum original distinctiveness required. Rather, this descriptive understanding is reinforced by the figurative meaning conveyed by the additional reference to the specific sport.

The Federal Supreme Court thus concluded that FIFA's two trademarks "QATAR 2022 (fig)" und "WORLD CUP 2022 (fig)" lacked inherent distinctiveness.

As a consequence, the Federal Supreme Court ordered the cancellation of all four trademarks from the register and referred the case back to the lower court to decide on FIFA's outstanding injunctive relief claim. Finally, based on the binding findings of the Federal Supreme Court, in June 2022 the lower court ruled in favor of FIFA, that the use of the trademarks "PUMA WORLD CUP QATAR 2022" and "PUMA WORLD CUP 2022" constitutes unfair conduct under the Swiss Unfair Competition Act and is henceforth prohibited in the course of trade.

It is noteworthy that, pursuant to its practice, the Swiss Federal Institute of Intellectual Property Office (IPI) denied distinctiveness to signs along the lines of "QATAR 2022" and "WORLD CUP 2022" – i.e., "place plus year" and "event plus year" – only in connection with goods and services directly or nevertheless closely related to the event. The IPI now considers adapting this practice to comply with the Federal Supreme Court's recent decision.

The first Supreme Court Case in Administrative Cancellation Proceedings and on Export Marks

In Switzerland, administrative trademark cancellation proceedings for non-use were introduced only in 2017. Before that, parties who wanted to challenge a registered trademark for non-use had to initiate (more) costly proceedings in civil courts. In its first judgment, rendered in administrative cancellation proceedings, in UNIVERSAL GENEVE v. BEAU HLB, the Swiss Federal Supreme Court also, for the first time, had to consider trademark use in relation to export (Case 4A_509/2021 of the Swiss Federal Supreme Court, November 3, 2022).

The case related to cancellation proceedings, initiated against the trademarks U UNIVERSAL GENEVE (fig) (Swiss trademark No. 329720) and UNIVERSAL GENEVE (Swiss trademark No. 410354); the former registered in 1984 for "watches of all kinds and parts thereof, jewelry"; the latter registered in 1994 for "watches, watch parts." The applicant based its claims for cancellation on the argument that "the use of the trademark for export," within the meaning of Art. 11 (2) of the TmPA (which reads: "Use in a manner not significantly different from the registered trade mark and use for export purposes also constitute use of the trade mark."), which can be considered sufficient use of the trademark under Swiss law, did not apply to the challenged marks, since they had previously been marketed in Switzerland and had thus not been exclusively used for export purposes. The respondent argued that Art. 11 (2) TmPA granted trademark owners, active in the export market, a relief by not requiring them to distribute the branded products in Switzerland. This would not, however, prohibit the simultaneous use of the trademark in Switzerland and in export.

WHY IT MATTERS |

|

In order to maintain the rights to a registered trademark, the owner must actually use it in connection with the claimed goods and services, within the territory of Switzerland (Art. 11 (1) TmPA) within a grace period of five years (Art. 12 TmPA). As stated above, according to Art. 11 (2) of the TmPA, the use for export purposes constitutes (sufficient) use of the trademark. However, that rule still requires use in commerce, albeit abroad, and that the use be genuine.

On the facts, after registering the trademarks, the proprietor BEAU HLB had initially used for the trademarks in respect of sales in Switzerland. After that within the reference period of the last five years (corresponding to the five-year grace period for use according to Art. 12 TmPA), the trademark owner marketed high value watches in Asia, after having affixed the protected trademarks to them in Switzerland. The sales comprised about 60 pieces, spread evenly over the reference period. The lower court found this to constitute genuine trademark use and thus to be sufficient for a right preserving use, even if only for certain of the claimed goods. With regards to the notion of "use for export purposes," the lower court observed that, according to doctrine and case law, the export mark concerned goods and services "exclusively" intended for export. It stressed the importance of respecting this "exclusivity" in order not to relativize the principle of territoriality. Based on the fact that the owner, during the reference period, had only used the trademarks for export purposes, it concluded that the requirement of exclusivity was met. It thus ordered the retention of the two trademarks, but reduced the claimed list of goods: For the figurative mark to "watches of all kinds" and for the word mark to "watches." UNIVERSAL GENEVE appealed this judgment to the Federal Supreme Court.

In its decision of November 3, 2022, the Swiss Federal Supreme Court dealt with the interpretation of Art. 11 (2) TmPA and the question as whether the definition of a trademark as export mark does require that the corresponding trademark has always and exclusively been used for export purposes only. In this context, it held that Art. 11 (2) TmPA speaks of a "use for export" without mentioning any exclusivity. However, both the legislative materials, as well as doctrine and case law, speak of goods, which are exclusively intended for export. The Federal Supreme Court then compared the Swiss legal situation with the EU, where, for example, Art. 18 (1) of the European Union's Trademark Regulation requires that "the mark (...) be affixed to the goods or to their packaging in the Union solely for the purpose of export." The court noted that the two marks were, in any case, only used for export during the relevant reference period.

UNIVERSAL GENEVE had assumed that a trademark should be registered either for use on the Swiss market or for marketing abroad, which, as the Federal Supreme Court stated, the trademark law does not provide for. Swiss trademark law does not mention export trademarks among the recognized varieties of trademarks (word, figurative, combined, etc.); nor does it make the application of Art. 11 (2) TmPA conditional on such a mention in the register. Following this logic would lead to an odd result: the proprietor would be forced to choose a commercial model of either Swiss market or export at the time of registration and this might restrict future plans

The Court concluded that it is irrelevant that the two trademarks were once marketed in Switzerland and only then appeared on the foreign market. Prior use in Switzerland did not prevent the presumption of "export use" during the relevant period, which occurred in a manner that preserves the protection of the trademarks.

The judgment left open how a simultaneous use of the trademark domestically and for export purposes would be assessed.

Finally, the Federal Supreme Court recalled that trademark rights can only be maintained through a public use of the mark, which was satisfied here since the Swiss watches had been exported to Hong Kong for sale in various Asian countries and had been subject to the usual competition for such sales.

Contributors: Lara Dorigo (Partner), Alexandra Bühlmann (Associate)

No legal or tax advice

This legal update provides a high-level overview and does not claim to be comprehensive. It does not represent legal or tax advice. If you have any questions relating to this legal update or would like to have advice concerning your particular circumstances, please get in touch with your contact at Pestalozzi Attorneys at Law Ltd. or one of the contact persons mentioned in this legal update.

© 2023 Pestalozzi Attorneys at Law Ltd. All rights reserved.