Navigating AI with Pestalozzi – Part 6: Employment

Key Takeaways

- AI, with its immense data processing capabilities, is a useful tool to increase efficiency in operational processes. When data on job candidates or employees are processed, however, various labour law provisions must be considered before and during the deployment of AI.

- The employer's AI applications may only collect and process data that concern the employee’s suitability for the specific job or are necessary for the performance of the employment contract.

- AI bias may reinforce human prejudices and cause AI applications to discriminate against certain employees. The employer must therefore keep a watchful eye on both the use of and decisions made by or based on AI.

- Under current Swiss law, employees have a right of co-determination regarding AI’s use for monitoring purposes. To employees, however, introducing AI to the workplace brings many uncertainties and can cause them to be worried about its deployment. By involving the employees from the beginning and informing and instructing them properly on the use of AI applications, acceptance, and trust in AI can be increased, and legal risks can be minimized.

Introduction: Uses for AI in the Employment Context

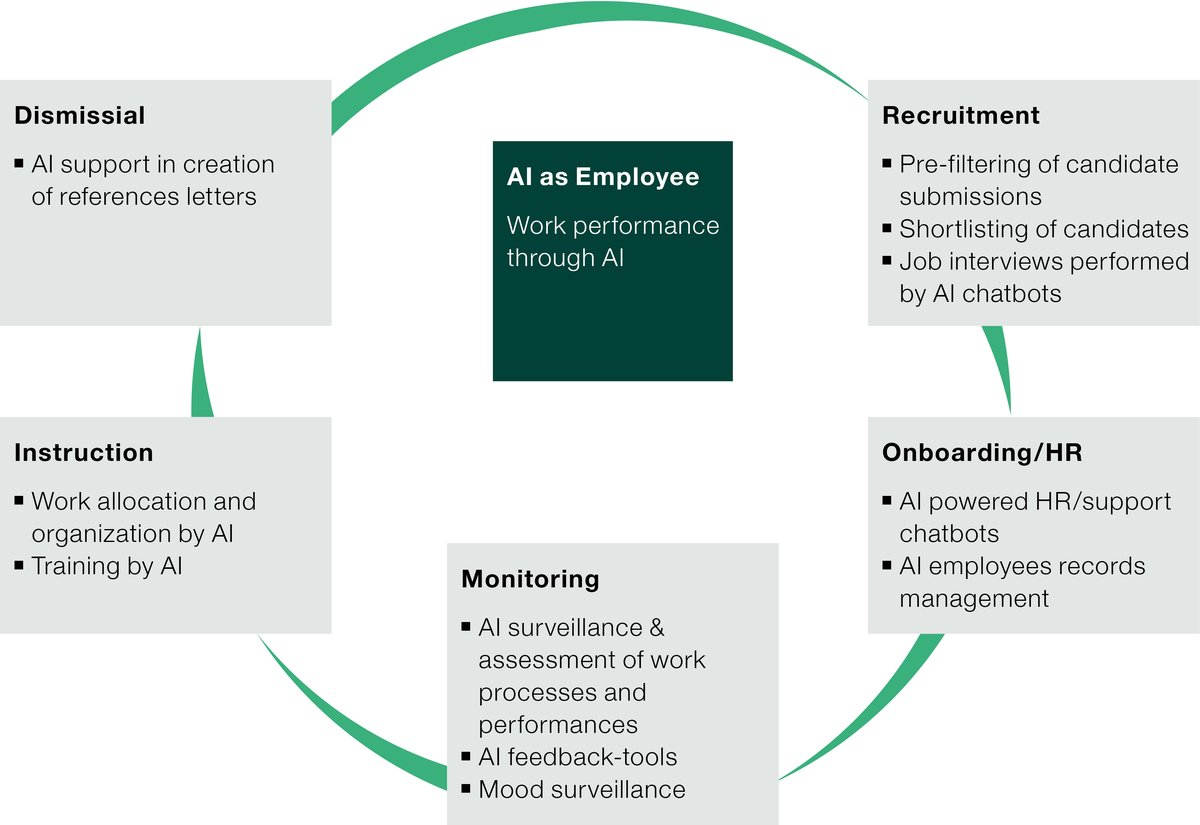

The rapid development of AI has a large impact on various aspects of the employment relationship. Indeed, AI applications can be used, and are increasingly being used for numerous purposes throughout the entire life cycle of employment relationships.

To name but one example, chatbot "Mya" by L'Oréal processes about two million CVs per year. Mya can process language, ask questions, and assess the answers to determine whether job candidates fit in well. During the ongoing employment relationship, AI applications can analyze work processes, monitor and analyze employee performance, or assign tasks to employees. Furthermore, AI applications can also be implemented in connection with dismissals. Of course, employees also use AI to perform their work services on their behalf.

AI has economic potential and brings various advantages for employers, for example, competitive advantages through talent acquisition, innovation, higher efficiency, as well as performance and cost reduction. AI applications, however, can also pose a variety of legal challenges. This overview aims at sensitizing employers to the various labour law related risks of deploying AI especially in the hiring and firing process and for surveillance, monitoring and instruction, and providing them with the necessary expertise to manage these risks.

Can AI Hire a Job Candidate or Fire an Employee?

AI can be a useful tool in people analytics, especially in the hiring and firing process, as it can process vast amounts of data, e.g., by filtering through CVs, scheduling and performing interviews, evaluating video or audio files, assessing emotions, analyzing behavior as well as movement quickly and – at least theoretically – making unbiased decisions based on facts alone. However, when using AI applications in the process of hiring new or dismissing current personnel, the employer must comply with various legal regulations.

Employer's Obligations Regarding Automated Individual Decisions

Switzerland does not prohibit automated decisions. According to Swiss data protection legislation, however, the responsible person must comply with specific obligations with decisions that (i) are solely based on automated processing of personal data and (ii) have legal consequences for the data subject or can otherwise significantly affect her/him. Such an automated decision is made when an AI application decides to (not) invite a job candidate to a job interview, (not) hire a job candidate or (not) terminate an employee and no individual subsequently reviews this decision.

In case of an automated individual decision, Swiss law requires the employer to actively inform the job candidate or employee about the process of automated decision making before or after such decision. The employer must also grant the job candidate or employee the right to present his/her opinion regarding the decision made. Finally, the job candidate or employee can demand that a human being review this decision (see also Part 4: Data Protection).

These obligations, however, do not apply if (i) the job candidate or the employee expressly consented to the automated decision making or (ii) the automated decision making is directly connected to the conclusion, or the performance of a contract and the job candidate or employee gets what he/she wants with said process. Thus, the employer need not comply with the aforementioned obligations towards the respective job candidate or employee if the AI application invites the job candidate to a job interview, hires the job candidate under the requested conditions, or does not dismiss the employee.

Prohibition of Employment Discrimination

One of the original aims of using AI in the hiring and firing process is to make decisions free of human prejudice by disregarding criteria such as origin, age or gender. AI is, however, only as good as the data respectively the algorithm that applies. As the AI's algorithm is programmed by human beings, it can also reflect their errors and prejudices and – through repetition – reinforce them (so-called "AI bias"). Therefore, like human beings, AI can also make wrong decisions based on incomplete or incorrect data. For example, if an AI application is trained based on a male-dominated workforce, it learns to downgrade the ranking of job applications from female job candidates and ultimately rejects them, even though they might be better suited for the job in question.

An employer should therefore make sure that the AI application is programmed so that it does not make discriminatory decisions based on gender, ethnicity, age, or other protected characteristics.

The Swiss Equality Act protects employees thoroughly against discrimination based on gender. It prohibits not only direct, but also indirect gender discrimination. Indirect discrimination is given if a gender-neutral regulation results at a significant disadvantage for members of a particular gender. In exceptional cases, discrimination may be justified on objective grounds, for example if the gender itself is an essential characteristic of the advertised job. Consequences of a violation of the Equality Act are the right of the employee to bring a declaratory, injunctive and/or prohibitive action as well as damage payments up to six monthly wages, depending on the type and severity of breach. Notwithstanding the forgoing, the protection of employees against discrimination in Switzerland is relatively modest outside of gender discrimination. Switzerland has no general equality act under civil law.

Forbidden Job Interview Questions

If an AI chatbot conducts a job interview, the same rules apply as for a job interview by a human being: In principle, the future employer has the right to enquire and collect certain information about a job candidate to form an impression about his/her skills.

However, besides the data protection regulations that must be observed (for further information: Part 4: Data Protection), in Swiss labour law, Art. 328b CO in particular sets strict limits: The information collected and processed must always have a factual and direct connection to the specific job profile or position to be filled, or it must be necessary for the performance of the employment contract. The employer must therefore ensure that the AI is programmed so that it does not process information unrelated to the future employment relationship. AI applications that measure, for example, the heartbeat or facial expressions of the job candidate are generally not compatible with Art. 328b CO. Also, questions regarding, for example, family planning, sexual orientation, union membership or political opinions are generally off limits. The same applies to questions regarding a person's health situation, debt or criminal record, unless they are specifically relevant for the job or position to be filled. However, ensuring the latter is likely to be difficult. The AI application would need to decide on a case-by-case basis whether a question is permissible, but AI is usually unable to do this. Moreover, due to the inner workings of large language models, there is a high risk that AI will make decisions about a person's eligibility for a job based on non-employment information simply because the AI has learned that this information might correlate with specific character traits or skills required for that job. For example, it may find from its training that being a member of a soccer team goes hand in hand with having great teamwork skills or being a triathlete goes hand in hand with determination. Although this might be true, soccer team membership is not causal for good teamwork, and participating in triathlons does not tell you anything about the candidate's resolve. Both relate to a leisure activity. It is questionable, therefore, whether an AI application processing such information is compatible with Art. 328b CO.

If the data collected and processed exceeds the scope of Art. 328b CO, defined by the specific employment relationship, this is considered a violation of personality rights. Due to the unilaterally mandatory nature of Art. 328b CO, the question of whether the job candidate's consent can justify this violation of personality rights is disputed in legal doctrine. The Swiss Federal Supreme Court, however, has affirmed that the job candidate's consent can justify a violation of Art. 328b CO. In any case, the employer must ensure that the job candidate has given his/her consent freely and only after being duly informed about the processing of his/her personal data by AI. Due to the imbalance in power in the employer-employee relationship, the standards for consent as a valid justification are rather high.

In case of a breach of Art. 328b CO, the job candidate has options for action, depending on the circumstances of the case. If the AI asks inadmissible questions during the job hiring process, the job candidate may refuse to answer or lie. In addition, the job candidate may be entitled to a damage claim or a compensation for pain and suffering.

AI Cannot Legally Engage or Dismiss an Employee

While automated decision making is not forbidden under Swiss law (see above), AI still cannot hire or fire an employee for the simple reason that it is not legally capable of acting in the sense of Art. 12 Civil Code. An AI application may decide and suggest that an employee should be hired or fired, but it must be the employer respectively the responsible natural person within a company who declares the intent to conclude or terminate an employment agreement.

Can AI Survey and Monitor Employees and Issue Instructions?

In addition to the deployment of AI in the hiring and firing process, large companies increasingly use AI to analyze, evaluate, and optimize workflow and operating sequences. Usually, this is done by permanent observation and precise analysis of work performance, working conditions, and fluctuations in demand. Based on this observation and analysis, an AI application may also be able to directly issue instructions to employees. In this way, for example, the AI application assigns urgent tasks to the employee who can complete the task the quickest, considering his/her skill level and location.

However, heightened surveillance and monitoring in the workplace can negatively affect the health of employees. If productivity is continuously increased, employees may begin to suffer from stress because of elevated work intensity and limited autonomy in decision making. In extreme cases, this can lead to unsustainable and unlawful working conditions.

Proportionate Surveillance and Monitoring

When using an AI application to survey and monitor employees, the employer must observe Art. 26 para. 1 of the Ordinance Nr. 3 to the Swiss Labor Act on health care of employees in particular. This provision intends to protect employees from surveillance measures unjustified by operational or other recognized purposes, and hence it limits the use of surveillance systems that monitor employees' behavior in the workplace. Surveillance systems that are used to solely or primarily keep a sharp eye on employees are not allowed. In contrast, if the employer uses the surveillance system primarily for another legitimate reason (such as ensuring undisturbed operational processes, quality assurance, occupational safety, the optimization of work organization or the productivity of personnel), its use is permitted if the health and freedom of the individual employee is not impaired, and the employer uses the system proportionately to the intended purpose. Therefore, it is very important that the employer precisely determines the purposes of the AI application used, and based on this, defines the required scope of data.

Furthermore, the employer's duty of care towards its employees according to Art. 328 CO and the requirements of Art. 328b CO regarding the collection of the employees' data also apply in the context of workplace surveillance and monitoring. The employer must therefore pay close attention to what data is collected from its employees and whether its processing leads to any form of unjustified discrimination or violation of personality.

In addition, the employer must look out for provisions under data protection law that limit surveillance. The employer must therefore:

- carry out the employee surveillance and monitoring transparently, regardless of the means chosen;

- inform the employee comprehensively and in advance about the surveillance and monitoring;

- delete the gathered data after the shortest possible period of time; and

- exercise utmost caution and restraint when analyzing data from wearables in the workplace, such as fitness wristbands, data glasses or sensors that collect health-related information, because this information is considered particularly sensitive data within the meaning of the Swiss data protection legislation, whose collection and processing is subject to particularly strict data protection restrictions.

Involving Employees

As stated above, for transparency’s sake, it is important that the employer provides its employees with comprehensive information in advance about AI applications used for monitoring them. In addition, employees have a right of co-determination ("Mitspracherecht"; but no right of co-decision) in matters of occupational health protection. AI applications that are used to survey and monitor employees are likely to be health-related and are therefore subject to the right of co-determination. The right of co-determination includes the right to be heard and consulted before the employer reaches a decision as well as the right to a statement of reasons for the decision if it does not or only partially hear the employee's objection.

Employees do not have a statutory co-determination right regarding the use of AI that goes beyond health protection. Before introducing AI in the workplace, however, the employer should examine whether any applicable collective bargaining agreement provides for employee participation regarding the integration of a new technology in the workplace (or generally restricts introducing AI).

Notwithstanding the foregoing, the employer must consider that there are many advantages of involving employees when it comes to deploying AI applications in the workspace: If employees are involved at an early stage, they can use their specialist expertise to assess whether the planned investments are sensible and expedient. If included from the beginning, employees will learn more easily how to use the AI applications correctly, but also how to improve the operation of the AI over time. For employees, the use of AI systems in the workplace is associated with many uncertainties but more involvement brings better understanding of the technology, and this will likely lead to an increase in trust and acceptance.

Finally, various parliamentarians and legal scholars consider the statutory participation rights of employees inadequate, particularly regarding the use of AI. In December 2023, a motion was put forward to strengthening participation rights of employees in the use of AI if it is used for recommendations, forecasts, decisions, etc. affecting employees or using employee data. Based on a mandate from the Federal Council to identify sector-specific need for action and possible options in connection with artificial intelligence, a legislative proposal is expected in 2025 (see Part 2: Regulation). Thus, a high likelihood exists that the legislative will propose an extension and reinforcement of employees' participation rights.

Instructions by AI

While it is possible and theoretically allowed under Swiss labor law to let AI give instructions to employees based on its surveillance and monitoring, the AI application must be programmed to comply with the prevailing legal order. The instructions must thus remain within the scope of what a human superior would be allowed to instruct. The AI application would have to decide on a case-by-case basis whether an instruction is permissible, but AI is – as mentioned above – to date usually unable to do this.

Can AI Issue a Reference Letter?

If the employer enters the appropriate prompts regarding an employee's functions and responsibilities, performance, strengths and behavior into an AI application, it can generate a useful template reference letter. This template can be adjusted and made concrete with only little effort to fit the specific employee. However, the employer is not dismissed from its duty to ensure that all the information about the employee is correct, complete and benevolent. Furthermore, the employer is responsible for the reference letter not including any cryptic phrases that may sound good but contain hidden negative messages about an employee and other coding methods. Therefore, every reference letter generated using AI must be reviewed carefully.

Of course, data protection principles also apply in this context (for further information: Part 4: Data Protection).

Finally, the reference letters must be wet ink signed by a person who is functionally and hierarchically superior to the employee. Hence, while AI can be a useful tool in its creation, it cannot fully take over the process of issuing a valid reference letter itself.

Change of Perspective: Are Employees Allowed to use AI to Perform their Work Services?

An employee's use of AI to perform work services is a highly debated topic. Questions especially arise with regards to liability (for further information: Part 3: Liability). In addition, the question arises as to whether employees are allowed to use AI at all considering the principle of personal performance. This principle says that employees must generally perform their work themselves (see Art. 321 CO).

The employer can and should decide whether and to what extent it provides its employees with a specific AI application and allows them to use it. The employer is allowed to permit the use of AI because the employees' obligation to perform their work themselves is non-mandatory and may be waived (see Art. 321 CO). Furthermore, the employer can also prohibit its employees from using AI. In this case, employees may not use AI to perform their work services. If they do so nevertheless, they breach their employment contract, which the employer can sanction under employment law, depending on the circumstances and the severity of the breach.

If the employer does not regulate the use of AI, the situation becomes more complex: Subject to any other agreement or practice, employees must perform their work personally (see Art. 321 CO). It is unclear whether employees breach this obligation if they use an AI application for their work performance. In 2021, the Swiss Federal Supreme Court was confronted with the question of whether an algorithmic application can fulfil the legal concept of a substitute. A bank had used its algorithmic system to perform all execution actions necessary to provide financial services to its clients. The Swiss Federal Supreme Court concluded that the AI application could not act as a substitute as it does not possess legal capacity. Rather, the Swiss Federal Supreme Court considered the AI as a tool. Against this background, a breach of the principle of personal performance could be denied. The decisive factor for the question of whether employees are allowed to perform their work by using AI in the absence of an employer regulation is likely to be the extent to which the employees use AI. If the employee uses the AI's output without critically reviewing it, a breach of the employee's obligation of personal performance and due care is likely. Depending on the circumstances of the individual case and the severity of the breach, sanctions may include a warning, ordinary termination or, in rare cases, termination with immediate effect. However, if the employee critically reviews the AI's output and intervenes in the AI's result, if necessary, the use of AI should not constitute such a breach per se.

Contributors: Andreas Lienhard (Partner), Nicole Sutter (Associate), Valerie Bühlmann (Junior Associate)

No legal or tax advice

This legal update provides a high-level overview and does not claim to be comprehensive. It does not represent legal or tax advice. If you have any questions relating to this legal update or would like to have advice concerning your particular circumstances, please get in touch with your contact at Pestalozzi Attorneys at Law Ltd. or one of the contact persons mentioned in this legal update.

© 2024 Pestalozzi Attorneys at Law Ltd. All rights reserved.